Mercari R4D (“R4D”) and Yamaguchi University worked together on the “Design Project for Value Co-Creation to Encourage Environment-Aware Behavior in Gen Z for a Circular Economy.” Running from October to November 2024, the project featured eight lecture-format sessions. In the first half, participants were asked to come up with individual ideas which they presented at a mid-term poster-format session. In the second half of the project, participants broke into four groups to refine the ideas in their mid-term presentations, which they presented in final presentations.

In the conversation in this blog entry, R4D Researcher Koki Kusano and Yamaguchi University Associate Professor Kazutoshi Sakaguchi review the session’s projects.

Overall review and thoughts on the project

Sakaguchi: So, let’s start by sharing a summary of this design project.

Kusano: Sure. This partnership project between R4D and Yamaguchi University started from the idea that it was important for individuals living in society to be self-motivated to act in a way that would realize a circular economy. In particular, we envision a future where it would be possible for individuals to take minor actions that will give them agency to be involved in and create services. We designed a process to make that vision happen and executed it together with Yamaguchi University. Lately, two topics that frequently surface as co-creation processes for service design are “participatory design” and “co-design,” which are views that focus on “design by stakeholders.”

I think that what we accomplished with this project is very close to that. Up until now, “design by stakeholders” was an approach that was limited to a very narrow band of people due to the degrees of skills and abilities involved. For example, when attempting to build any service online, things like programming and design skills are hurdles. However, due to the maturation of various types of tech, such as today’s information society and the development of AI, I believe that virtually anyone can break through these barriers. With this serving as the background of the project, we tried to incorporate AI into our process.

Orientation: R4D Researcher Kusano delivering a lecture

Orientation: R4D Researcher Kusano delivering a lecture

Sakaguchi: When you actually looked at the student’s output, was there anything that struck you?

Kusano: First of all, looking at the content, I got the sense that there wasn’t a very big difference between what they described and the things that I had been interested in when I was a student or the things I had been worried about when it came to getting a job. However, what I personally found interesting was observing what you could call the layers of shifting trends, such as how people spend their time and money as society changes.

Sakaguchi: In their individual work in the first half of the session, we asked the students to provide information from their point of view. I was surprised by the amount of feedback about how hard daily living is for them.

Orientation: Defining the line between what is and what isn’t garbage

Orientation: Defining the line between what is and what isn’t garbage

Kusano: The mid-term presentations contained a number of innovative suggestions, and as you can imagine, the ideas that came from students’ intrinsic drive struck me as really sharp.

Sakaguchi: I have to agree. The presenter would state their case passionately, and everyone else just listened with a look of wonder on their face. (laughs)

Kusano: I thought that these sorts of innovative topics that came up in the first half were an interesting indication as to how the initiative would progress. In the second half of the initiative, I got the sense that the ideas had matured as proposals, but you could say they had also ended up becoming a little more abstract. In other words, I had the impression that the proposals were direct approaches that almost anyone could have conceived, and that was also one slightly difficult point. From a process design perspective, the students were given a lot of freedom, and that made me wonder if there would be some inconsistencies. What did you think?

Sakaguchi: I have to agree. While it was good to see a lot of individual ownership in the first half of the project, when it came to the assigned topic of circulation, I thought there was a bit of an issue when we examined what was ultimately being circulated. Everyone had their own ideas about what circulation meant. Some interpreted it as a reduction in garbage, and others saw it as things like the circulation of skills and knowledge. This is why I thought it would have been better to discuss this point a little more carefully and to make time to clarify what their ideas around circulation meant to them.

Kusano: I think they can do better at finding things like the exact contact points between their ideas and the circular economy and at shaping their ideas on what they believe the scope of a circular economy to be in the first place.

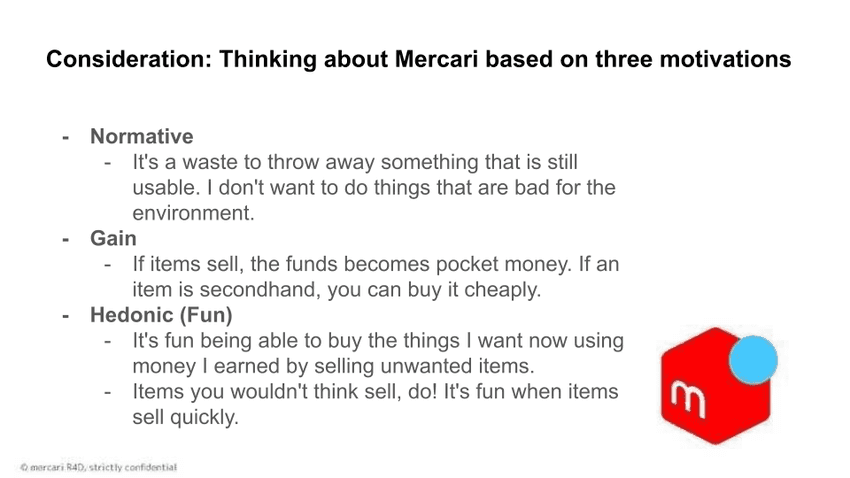

Normative, gain, and hedonic considerations influencing pro-environmental behaviors

Sakaguchi: As a reference for this project, you pointed to an academic paper on normative, hedonic, and gain goal frameworks in pro-environmental behaviors. The research applies the goal framing theory of behavioral psychology in the context of pro-environmental behavior. In concrete terms, motivators like norms, gain, and hedonic pleasure are contributing factors. In particular, when there are no concrete norms established, people tend to behave hedonically. The design we were looking to attain was one that would allow hedonic pro-environmental behavior in the absence of such norms. Could you share any findings you uncovered from this research theory and the project’s output?

Goal-framing theory in pro-environmental behavior

Goal-framing theory in pro-environmental behavior

Kusano: Frankly, I’m not sure how well our inquiries came together in the students’ minds and were put to use. However, looking at the suggestions they came up with, I would guess they were trying to create a somewhat fun atmosphere.

Sakaguchi: I see.

Kusano: Rather than coming up with really serious solutions to the problems, they incorporated a touch of wit and harm to their solutions. I think we ended up with something very different from what you’d call approaches that seriously lean into environmental issues. We talked about the three goals of normative, gain, and hedonic frameworks and about the importance of balancing them, but I was left wondering whether what we said on the topic had an impact on them. What was your opinion of this?

Sakaguchi: As you can imagine, I think the fact that they were conscious of norms meant that they only became aware of the whole topic in the second half of the project. Even as I listened in on their group work conversations, I thought there were quite a lot of opinions being tossed back and forth about the ideal way things should be. For example, there was one idea raised for a service that would use the composting of kitchen garbage to circulate the kitchen scraps produced in students’ homes into soil enrichment in cooperation with a school cooperative and the university’s agricultural department. I thought that where the students tried to work via the school’s cooperative and to use circulation effectively to resolve a problem showed a very high awareness based on norms.

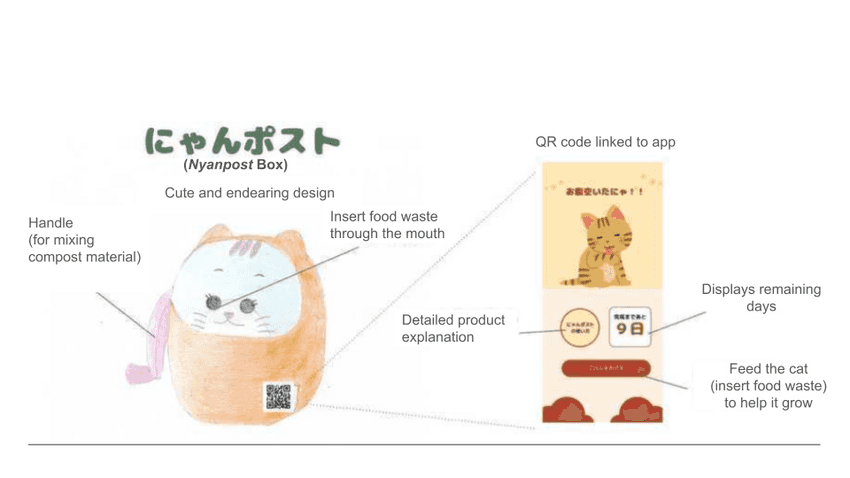

Kusano: On the other hand, rather than being completely serious, I think one point to note is that you could really see them reaching for the hedonic aspect of things, such as with the cat interface presented at the end.

Concept drawing of the “Nyanpost Box”

Concept drawing of the “Nyanpost Box”

Kusano: What I’d like to talk about next might take us away from the goal frameworks. In essence, Mercari’s anonymous matching of individuals instills peace of mind and value. However, when it comes to actually working together to solve social issues like the ones we looked at, I felt that there needed to be a certain atmosphere that would give the students a certain level of visible proximity. That way, even if they were not completely acquainted with each other, they could still look to specific trustworthy labels, like “fellow student”, or by matching through a co-op. Users of an existing service don’t mind using that service anonymously, but one somewhat interesting thing that I discovered as I worked on this initiative was that when the students worked on this social issue, they uncovered the potential of these kinds of limited-scope teams.

Sakaguchi: So they deliberately use the existing ecosystem in reverse. There were those who also took that approach, and it made me think that an organization developing into something that learns from norms would be another possible answer to achieve a circular economy.

Kusano: Under the existing system, there remain a variety of risks, but if there is potential there, it would entail something like adding a system geared for the circular economy while skillfully updating the current norms. I sense a lot of potential in this idea.

Gaining a window into Gen Z’s perspective during the project

Sakaguchi: For this project, we talked about how we can’t seem to get a grasp of Generation Z (or “Gen Z”) users, and the students who completed the project were members of that very generation. I think they shared a variety of ideas from their own points of view as stakeholders. Having listened to the various ideas they had, could you tell us about any traits you noticed for their generation, if any?

Kusano: I’d actually like to ask you about this first. You’ve spent a lot of time working on this.

Sakaguchi: Looking at the traits of the students in my faculty, there is a vast multitude of perspectives, and many people have a high interest in multicultural understanding. Some had just come back from a foreign exchange program, and I think they came up with ideas that incorporated a variety of the experiences they had while overseas.

Kusano: I see. One impression I had was that they know what they like and have no qualms about telling you about their preferences. They can set aside other people’s opinions for the moment to tell you precisely what they like. I think this sort of ties to ideas of diversity and diverse perspectives. Another thing that I noticed was how they value experiences. Rather than looking at things for their surface value, I felt that their approach was more like, “what experience will I gain by going through this?”. They bring the same concept to the ideas that help them when looking for work. They’re like, “if I’m going to look for work either way, I want my job search to be a valuable experience.” This was one point that I found interesting.

Sakaguchi: They have a definite desire to use their own limited time and experience more normatively, and if there is a mechanism that will support them, they might be more likely to choose it.

Program participants at work on a sprint review

Program participants at work on a sprint review

Kusano: This is why, generally speaking, in the professional world we talk about things like time-performance, but I feel like there are two extremes to this: One that focuses on time-performance and getting things done quickly, and one where a person wants to take their time because it nourishes their experience.

Kusano: In addition, rather than concentrating on making a strong connection with one person, they might, for instance, share time to connect with people studying the same subject, and by providing stimulus to each other, enrich the time they spend on improving their performance. Regarding a certain hobby, they might connect with a community out of a desire to improve themselves. Alternatively, if there are a number of areas they want to look at, for each of those areas, they try to communicate as best they can to connect with others and enjoy their time. I think this is better than having a buddy who constantly accompanies you for each of the things you do.

Sakaguchi: Also, while that applies generally, as you can imagine, sharing is fundamental to Gen Z. And so sharing is simply included nonchalantly in their ideas from the start. They still don’t know whether doing so is a good or a bad thing. For our generation, if anything, you could say that we lived through a time when we had a variety of experiences without networks, and now we’re contemplating a world of connections from that point of view. When I listen to the students talk, everything is premised on people being connected. So, for example, if they are not connected or become disconnected, they question whether they’re able to proceed with their suggestions. As a member of a different generation, I found this a little foreign.

Kusano: Precisely because the activities are premised on connections, controlling the extent to which people are connected and deliberately reducing the extent of connections for a time becomes easy to propose as an idea. However, as an end solution, it comes down to a solution premised on certain degrees of sharing and connection.

Sakaguchi: It does indeed come down to that. So, perhaps an unconscious bias that connections exist might also have been a trait of Gen Z.

Editor’s comments:

To members of Gen Z like us, reaching out to others on social media might just be a natural first step. I think one important element is to try and break down the conventional wisdom and biases we currently hold. I would like to do my best to question conventional wisdom. (By: Miharu Oki, 3rd year student of the Yamaguchi University Faculty of Global and Science Studies)